STAKEHOLDER INTERVIEWSPerspectives from 15 global health leaders on GHIT's catalytic role and

Japan's transformational contributions to global health R&D

POLICY

03

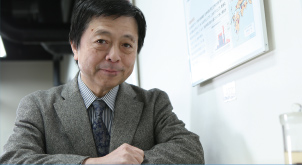

Hon. Prof. Keizo Takemi

Member, House of Councillors, Japan

Chairman, Special Committee on Global Health Strategy, Liberal Democratic Party

“How Japan has consistently played a pioneering and leadership role in shaping global health policy and strategy.”

What is the difference between international health and global health?

The 1990s saw the rapid development of interdependent relations among people, goods, capital, and information across national boundaries, in what is known as globalization. This phenomenon also brought with many interconnected health-related issues and problems that cannot be solved by one country alone, particularly infectious diseases. Along with global concerns about dangerous infectious diseases that know no borders, awareness of the need for a common framework under which the international community can work together to address these challenges has also grown. Up until the 1990s, this field was called “international health.” Countries tackled health care and medical issues through multilateral aid schemes with advanced nations, providing bilateral aid to low- and middle-income countries and contributions and capital to international organizations.

Then, starting around 2000, new players began to participate in this field, such as international charitable organizations like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, innovative public-private partnerships, non-governmental organizations, and nonprofit organizations. This approach had an extraordinary impact. Nations and international organizations no longer had to work independently on health issues that didn't respect geographic borders. Instead, many like-minded organizations and groups formed dynamic partnerships to tackle these issues, changing the landscape. Today, we call this field “global health,” and it has become one of the most important fields in the world, with several different agendas.

What is the history of Japan's leadership in global health policy and strategy?

Japan became involved in the field of global health in a major way through the G7 and G8 summits. Japan raised the issue of infectious diseases for the first time at the Summit held in Kyushu and Okinawa in 2000 where the government announced the Okinawa Infectious Diseases Initiative, committing three billion US dollars in funding to support the initiative. Japan's leadership on this eventually led to the establishment of The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

In 2008, Japan hosted the Hokkaido Toyako Summit, where the government strongly emphasized the need for health systems strengthening in the global health field. Japan played a pivotal role in making this new theme mainstream in global health. At the time, it was noted that disease-specific—or “vertical”—approaches, which focus only on infectious diseases measurements, are insufficient to solving comprehensive health and medical issues in low- and middle-income countries. In addition, there was a growing awareness of the need to strengthen health systems overall, including through capacity development of health care professionals. Given this context, Japan proposed that global health issues could be more effectively addressed by strengthening the horizontal axis of health systems, in addition to the vertical axis of disease-specific approaches using traditional infectious disease measures and vaccination. Health systems strengthening has since become the one of the most important themes in the global health arena.

At the Ise-Shima G7 Summit in 2016, Japan proposed reinforcing the global health architecture to strengthen responses to public health emergencies in peacetime at the local, national, and even global levels, based on the outbreaks of infectious diseases such as Ebola and Zika, which had recently made a serious impact on public health and the world economy. Moreover, Japan strongly appealed for a collaborative international framework to help create a more robust and sustainable health system in each country. The end goal is universal health coverage, another critical health theme that Japan has been promoting.

This is how Japan has consistently played a pioneering and leadership role in shaping global health policy and strategy. More recently, Japan has also aggressively engaged in global health R&D, helping to create new innovations by leveraging Japan's cutting-edge pharmaceutical technology and capability. The GHIT Fund has played a catalytic role in launching and accelerating these activities.

“In today's global society there is a lot of mobility among people and goods; we can't afford to think of infectious diseases as occurring only on distant shores. Japan needs to be actively involved in dealing with this issue.”

What is the rationale for Japan's leadership in global health?

The first reason is philosophical. During the Obuchi Cabinet of the 1990s, Japan revised its Official Development Assistance (ODA) charter. Human security was included in the new charter as one of Japan's fundamental foreign policies, forming a foundation for Japan's international cooperation philosophy. Simply put, this meant that Japan was focused on expanding, as much as possible, the options given to people to allow them to lead meaningful lives. Based on this line of thinking, when someone's health is poor, they have limited options for receiving education or job training, or even work opportunities. While health is not the only factor critical to a meaningful, productive life, all other factors are adversely affected when a person's health is damaged. As a result, health was recognized as having a central role in promoting human security. This became the fundamental philosophy underlying Japan's efforts at the Okinawa, Toyako, and Iseshima G7 and G8 summits.

The second reason is to leverage Japan's strengths for the global good. Life expectancy in Japan is among the highest in the world—for both women and men. Additionally, Japan's health, medical, and long-term care policies and systems are among the best and most progressive in the world. Leveraging these strengths for health and medical issues at the global level has become an important pillar of the country's international contributions.

The third reason is our contribution to low- and middle-income countries. In addition to Japan, many other countries are rapidly aging. In the case of Japan, our dependent population index peaked around 1960, yet we remained fairly flat after that time, until about 2000. During that period, little burden was placed on the dependent population, such as the elderly and children, which meant the country enjoyed forty years of extremely good fortune. In 1961, Japan implemented national universal health insurance and pension systems. In the 1980s, Japan created aging policies, and implemented long-term care insurance in 2000 to respond to the needs of our rapidly aging population.

However, other Asian countries have not seen changes in their dependent population index similar to Japan's U-shaped index curve. Moreover, their population dynamics predict a sharp V-shaped change with a rapidly increasing aging population reaching a peak in the near future. In this case, they do not have the same luxury as Japan in taking forty years to prepare for what is to come. Furthermore, Asian countries are expected to have a massive aging population prior to achieving universal insurance and health care coverage systems. In order to help address these problems now, Japan must make major, comprehensive contributions to these other countries in Asia.

“I believe that having global public–private partnerships from the very beginning has been a key factor in the GHIT Fund's success to date.”

R&D has recently become another important pillar of Japan's global health policy. What is the rationale for Japanese R&D support for infectious diseases that are not prevalent domestically?

There are several reasons for this. First, even if we are talking about drugs that are predominantly needed in low- and middle-income countries, it is important to recognize that infectious diseases like Ebola can be carried to Japan. In today's global society there is a lot of mobility among people and goods; we can't afford to think of infectious diseases as occurring only on distant shores. Japan needs to be actively involved in dealing with this issue.

The second reason is that infectious diseases are have a drastic impact on the economic development of low- and middle-income countries, which in turn carries economic and geopolitical implications for Japan. For example, if a country that exports to Japan ceases to function properly or its economy stalls, Japan will be impacted both politically and in its business relations. Japan, as a developed and mature nation, has a responsibility to pro-actively address and contribute these challenges.

The third reason is that it is necessary to create an environment and opportunities that allow Japanese pharmaceutical companies to leverage their advanced technologies to make global contributions. They cannot only do business in the domestic marketplace; Japanese businesses are also expected to work globally, including in low- and middle-income countries. In doing so, I believe that Japanese companies will be able to increase their international competitiveness. In addition, Japanese pharmaceutical companies can create new business opportunities over the mid- to longer-term. Creating and delivering new drugs for diseases in low-and middle income countries will help Japan and its pharmaceutical industry secure an important position in those countries' markets as they grow and expand. My understanding is that GHIT's efforts are the first step in that direction.

How were you involved in GHIT's establishment?

When launching the GHIT Fund, Dr. Slingsby (the founding CEO of the GHIT Fund), who worked for Eisai at that time, collaborated with other Japanese pharmaceutical companies to create the basic concept for the Fund. Then they collaborated with Gates Foundation and other founding partners to establish a clear structure.

During this time, I worked with the Government of Japan to help facilitate its involvement. It was important for us to make sure GHIT had an innovation delivery support function from the outset, so that people in low- and middle-income countries could actually use our products. In other word, the goal was not simply to create innovation, but also to ensure access to and appropriate use of that innovation.

However, drug development falls under the purview of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and jurisdiction for delivery involves the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and international organizations, so the Ministry of Foreign Affairs also needed to be involved. Accordingly, realizing GHIT's vision required both ministries to provide funds—in fact this represented the first time two ministries funded a project jointly. It was extraordinarily difficult to make both ministries fully understand the concept of the GHIT Fund and help with funding. Fortunately, we were successful. Both ministries are deeply involved in GHIT's governance. In the future, continuous effort from the Japanese government will be critical to ensuring that the GHIT Fund grows as a flagship model for international public–private partnership and innovation.

What do you see as GHIT's progress to date? What challenges and opportunities do you see in GHIT's future?

I think a major success of the GHIT Fund was the launch itself. Even with just the public side of the public–private partnership, there was collaboration between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Further, on the private side, there are not only pharmaceutical companies but also notable foreign foundations participating, such as the Gates Foundation and Wellcome Trust. I believe that having global public–private partnerships from the very beginning has been a key factor in the GHIT Fund's success to date.

We have not had any tangible results yet (in terms of products on the market), but the drug development pipeline is progressing steadily, even with relatively limited funding. Our scope of activity will also further expand. It pleases me much more than I had initially thought it would to have Japanese pharmaceutical companies take interest and participate in the GHIT Fund. I expect more Japanese pharmaceutical companies to participate even more actively in the future.

However, we are coming to a critical moment. It is important that we reach our initial goal, which is to produce and ensure the delivery of drugs and vaccines to low- and middle-income countries. Based on that aim, a new goal for the GHIT Fund would be to create a delivery support system, for example, through existing and new partnerships with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and other international organizations. Moreover, I expect that GHIT can further strengthen its governance to appraise the entire innovation spectrum, from discovery, to development, to delivery.

“I expect that GHIT can further strengthen its governance to appraise the entire innovation spectrum, from discovery, to development, to delivery.”

What drew you personally to the field of global health?

There were a number of coincidences that led me to work in this field. I was originally studying international political science at university. It just so happened that I became a member of the House of Councilors and began working on health and medical system reforms for Japan. Through that process, I think I naturally gained an awareness of issues with the health and medical system from an international perspective.

Further, my father, in his later years as Chairman of the Japan Medical Association, created the Takemi International Health Program at the Harvard School of Public Health, which promotes and supports Harvard-based research on international health. It financially backs researchers—both overseas and in Japan—and contributes to the creation of programs. Through these activities, he was able to support global health-related academic activities over the course of many years, and I personally had an opportunity to study global health policy there. Through these experiences, I became aware of the new field of global health, and it became tied to my activities as a politician. That led to my interest and involvement in today's global health initiatives.

I'm happy that I have been able to realize many of my goals. In the future, I would also like to focus my energies on creating platforms that make global contributions by leveraging the various insights and expertise that Japan, an advanced country with an aging population, has accumulated, in advance of populations aging throughout the rest of Asia.

The affiliations and positions listed in this interview are at the time of publication of the interview in 2017.

- Biography

- Hon. Prof. Keizo Takemi

Member, House of Councillors, Japan

Chairman, Special Committee on Global Health Strategy, Liberal Democratic Party

Keizo Takemi, LLM, is Chairman of the Special Mission Committee on Global Health Strategy for Japan's Liberal Democratic Party. He is also Senior Fellow at the Japan International Exchange Center and Visiting Professor at Keio University, Nagasaki University, and Minobusan University. Previously, he served as Senior Vice-Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare in the Government Japan, where he has also been Parliamentary Secretary for Foreign Affairs. Prior to his role as Vice-Minister, he chaired key committees in the House of Councillors, to which he has been elected four times. He has been a Professor in the School of Political Science and Economics at Tokai University, a Visiting Fellow at Harvard University's School of Public Health, and a TV Anchor in Japan.

http://www.sangiin.go.jp/japanese/joho1/kousei/eng/members/profile/5995043.htm

STAKEHOLDER INTERVIEWSARCHIVES

FUNDING

-

01

Dr. Naoko YamamotoSenior Assistant Minister for Global Health,

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

#

-

02

Dr. Hannah KettlerSenior Program Officer, Life Science Partnerships

Global Health Program, Office of the President

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

#

-

03

Prof. Stephen CaddickDirector, Innovations Division,

Wellcome Trust

#

DISCOVERY

-

01

Dr. David ReddyCEO

Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV)

#

-

02

Mr. George NakayamaRepresentative Director,

Chairman and CEO

Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited

#

-

03

Prof. Kiyoshi KitaProfessor Emeritus, The University of Tokyo

Professor and Dean, Nagasaki University School of Tropical Medicine and Global Health

#

DEVELOPMENT

-

01

Mr. Christophe WeberRepresentative Director, President and CEO

Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited

#

-

02

Mr. Yoshihiko HatanakaRepresentative Director,

President and CEO

Astellas Pharma Inc.

#

-

03

Dr. Nathalie Strub WourgaftMedical Director

Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi)

#

ACCESS

-

01

Dr. Jayasree K. IyerExecutive Director

Access to Medicine Foundation

#

-

02

Mr. Tetsuo KondoDirector

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

Representation Office in Tokyo

#

-

03

Dr. Aya YajimaTechnical Officer

Malaria, other Vectorborne and Parasitic Diseases Unit

Division of Communicable Diseases

World Health Organization Western Pacific Regional Office

#

POLICY

-

01

Dr. Mark DybulFormer Executive Director

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS,

Tuberculosis and Malaria

#

-

02

Dr. Seth BerkleyCEO

Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance

#

-

03

Hon. Prof. Keizo TakemiMember of the House of Councillors of Japan

Chairman, Special Committee on Global Health Strategy

of the Liberal Democratic Party's Policy

#