STAKEHOLDER INTERVIEWSPerspectives from 15 global health leaders on GHIT's catalytic role and

Japan's transformational contributions to global health R&D

ACCESS

03

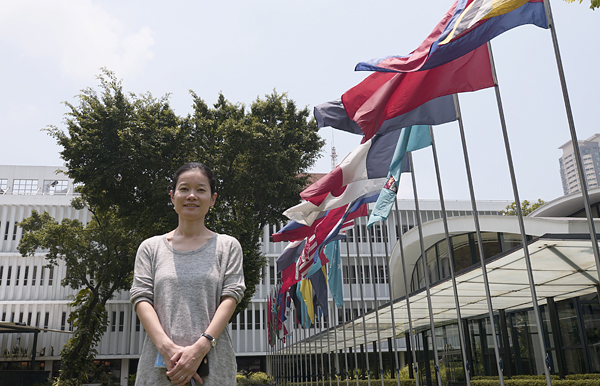

Dr. Aya Yajima

Technical Officer

Malaria, other Vectorborne and Parasitic Diseases Unit

Division of Communicable Diseases

World Health Organization Western Pacific Regional Office

What are neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), and what is their global impact?

The term neglected tropical disease, or NTDs, describes a group of infectious disease conditions primarily prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas. Currently more than 1 billion people in 149 countries and territories are estimated to be affected by NTDs, with a resulting economic loss of billions of dollars each year. NTDs are widespread in Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and South and Central America, predominantly among the population in poverty who are forced to live in close contact with vectors and animal reservoirs such as livestock. Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines NTDs as disease conditions that:

Many NTDs are parasitic diseases transmitted to humans through insects or other vectors, such as mosquitoes, flies, kissing bugs, or snails. Some, however, are caused by bacteria or viruses.

Until 2016, WHO classified 17 diseases as NTDs. However, inclusion of mycetoma was endorsed by the World Health Assembly in May 2016, and three additional diseases were further added to the list in 2017, bringing the total to 21.

What makes a disease “neglected”?

NTDs are “neglected” for a number of reasons. First, mortality rates associated with NTDs are not necessarily high as those of HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis – the major infectious diseases that receive the greatest resources and attention worldwide. Second, NTDs typically affect individuals who live in poverty for an extended period of time. In other words, those who are residents of developed nations are rarely affected even while travelling to endemic areas. Third, people most affected by NTDs are the poorest of the poor in low- and middle-income countries. Because they cannot afford treatment there is little financial incentive for the private sector to invest in R&D of those treatments. For all these reasons, and because of a perception that the impact of each individual NTD is rather small, these diseases have received little attention from the international community for a long time.

However, the reality is that NTDs make significant health and socioeconomic impacts on endemic populations and countries. NTDs typically cause severe physical deformities and other permanent. For example, trachoma and onchocerciasis cause blindness, and lymphatic filariasis (elephantiasis) causes serious deformation of feet and scrotum. Treponemal infections (such as yaws), leprosy, leishmanisis, and mycetoma involve severe skin morbidity. As a result, affected individuals might not be able to work or get married. They might suffer from discrimination and prejudice in the society and cause significant psychological burden.

Some NTDs also affect physical and cognitive development during critical growth periods of children. This might lead to reduction of the labor force in countries where NTDs are prevalent in the future. While NTDs in general do not immediately kill infected individuals, their socioeconomic impacts are significant.

“Clearly defining the strategies to eradicate, eliminate and control NTDs and presenting the available tools and the remaining needs to realize such strategies helps donor agencies provide financial support and private sectors and other partners find concrete ways to contribute to such endeavor.”

How are Japan and the international community responding to NTDs?

Not all NTDs have necessarily been “neglected”. For some, such as lymphatic filariasis, guinea worm disease, onchocerciasis, and yaws, World Health Assembly resolutions calling for global efforts to eradicate or eliminate these individual diseases date back to the 1950s.

At the G8 Summit in Denver in 1997, the then Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto indicated that parasitic diseases represent one of the major causes of poverty globally and called for global efforts to combat these diseases. This triggered an increased interest and a subsequent response from the global community. However, as I mentioned earlier, the number of people infected with each individual parasitic disease and the associated mortality are relatively low to that of other major infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis. Therefore, they remained of less priority on the global health agenda and were simply included under the category of “Other Diseases” in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of the United Nations.

However, recognition gradually began that these “Other Diseases” collectively put more than 1 billion people at risk of infection and cause a huge burden in global health and that many of the strategies for eradication, elimination and control of these diseases have commonality and thus implementation of such strategies in an integrated and coordinated manner across multiple diseases is more cost-effective and synergistic. This led WHO to officially redefine the group of diseases as NTDs and establish the Department of Control of NTDs within WHO in 2005, which aim to contribute to reduction of world poverty and achievement of MDGs through eradication, elimination and control of NTDs.

In 2007, WHO held the first Global Partners Meeting on NTDs where the global burden and impact of NTDs, and strategies and tools necessary for elimination and control of NTDs were laid out. Evidence-based vision and policy directions were presented to demonstrate that NTDs can be eradicated, eliminated, or if not, controlled. Through this process, WHO strengthened partnerships and engagement with donor agencies, partner organizations, academic and research institutions and experts. Clearly defining the strategies to eradicate, eliminate and control NTDs and presenting the available tools and the remaining needs to realize such strategies helps donor agencies provide financial support and private sectors and other partners find concrete ways to contribute to such endeavor. In that sense, grouping (then) 17 different tropical diseases as NTDs was a groundbreaking idea.

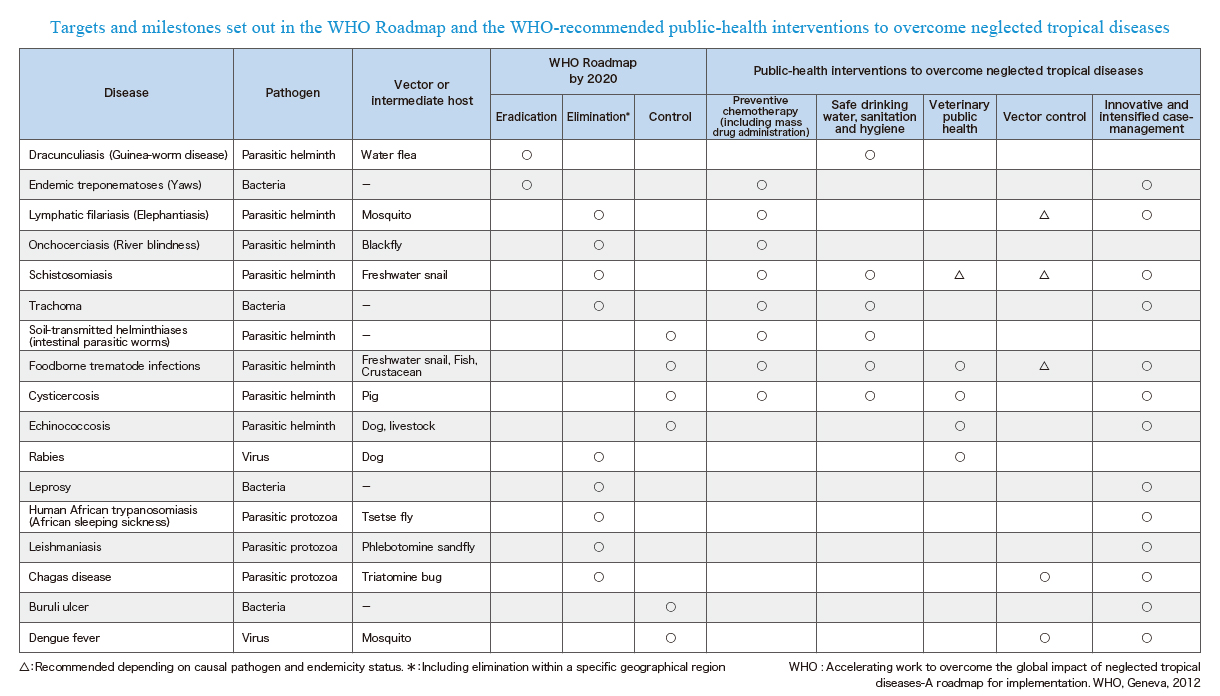

In 2012, WHO launched a roadmap towards achievement of eradication, elimination and control goals of NTDs. This roadmap set out the 2020 goals, targets, milestones and strategies to achieve them for each of 17 NTDs, and thus has been serving as a guide and direction for all stakeholders involved in the fight against NTDs since then. The key public health strategies for NTDs include:

- Preventive chemotherapy (including mass drug administration);

- Safe drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH);

- Veterinary public health;

- Vector control; and

- Innovative and intensified case-management.

Disease conditions defined as NTDs can be eradicated, eliminated or controlled by implementing one or a combination of these strategies. Looking at the recommended strategies and targets across diseases, you can clearly see what we are aiming for by 2020 and what combinations of strategies can be most effectively integrated and coordinated across diseases.

Further in 2012, a public-private partnership of an unprecedented scale in global health (commonly known as the London Declaration) was launched towards achievement of the 2020 NTD roadmap by 13 global pharmaceutical companies, WHO, World Bank, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, various academic and research institutions, and other partners. The GHIT Fund was then founded in 2013, through which Japan also increased its commitment to NTD elimination and control both independently and as part of the major global efforts described here.

“Even in countries that have achieved elimination status, their job is not over.”

Please tell us about efforts of the WHO Western Pacific Regional Office and the progress and future prospects of elimination and control of NTDs in that region.

Fourteen NTDs are endemic in 28 countries and territories in the WHO Western Pacific Region. Among those 14 diseases, the greatest advancement has been in elimination of lymphatic filariasis. The Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis (GPELF) was launched in 2000, preceded by the Pacific Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis (PacELF), under the strong leadership of Dr. Kazuyo Ichimori (currently Visiting Professor at Nagasaki University and formerly a scientist in charge of the GPELF at WHO Headquarters).

Dr. Ichimori had devoted her life’s work to the elimination of lymphatic filariasis in Pacific Island countries long before she moved to WHO Headquarters. She launched the PacELF based on her idea that it would be much more efficient and effective to formulate elimination strategies and manage implementation of interventions for the region rather than each individual small island nation managing on its own.

Help us understand what it takes to eliminate lymphatic filariasis.

With some exceptions, the transmission of lymphatic filariasis can be interrupted most effectively by mass drug administration. This strategy has proved effective in the Western Pacific Region where seven countries have validated by WHO as having eliminated lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem over the past two years. Six out of these Seven countries are Pacific Island countries under the PacELF. We believe that most of the countries in the Western Pacific Region are on track for elimination of lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem by the 2020 global target.

Is mass drug administration an important strategy for all NTDs?

While mass drug administration alone can be effective as a primary strategy for elimination of some NTDs, there are many other NTDs for which a combination of multiple strategies is required. For example, schistosomiasis, which is currently widespread in China and the Philippines, infects both humans and other mammals, such as buffalos and cattle. In such case, mass drug administration targeting humans alone is insufficient. Strong partnership and collaboration with WASH and the veterinary health sector is essential.

The global focus for elimination and control of many NTDs so far has indeed been preventive chemotherapy (or mass drug administration). Preventive chemotherapy intervention allows rapid reduction in prevalence of many of the NTDs with inexpensive, safe, broad-spectrum medicines. In many parts of the world, scale-up of preventive chemotherapy intervention still remains the priority. The Western Pacific Region, on the other hand, already has a long history of implementing preventive chemotherapy intervention and is advancing to the next stage with new challenges are faced ahead of other WHO Regions. The WHO Western Pacific Regional Office (WHO-WPRO) has an important role to ensure that countries facing new challenges at varying stages along the road towards elimination and control of NTDs are guided appropriately to move a step forward and also to provide examples and guidance for countries in other Regions.

“I wish to continue working behind the scenes to help as many countries as possible to achieve the NTD roadmap goal for as many diseases as possible.”

What weapons does the future fight against NTDs require?

Even in countries that have achieved elimination status, their job is not over. For example, patients in these countries suffering from lymphedema and hydrocele will remain and continue to live with this residual morbidity for the rest of their lives. We need to make sure that the health system provides a minimum package of care for such patients, and that such care is sustained over a long period. Otherwise, these patients will be left behind once activities specific to lymphatic filariasis elimination are terminated.

Another issue is post-elimination surveillance. There is a significant movement of people and animals across borders in Asia and the Pacific Ocean as a result of globalization. For example, many people from Bangladesh and the Philippines move to Pacific island countries as migrant workers. Lymphatic filariasis is endemic in both Bangladesh and the Philippines. There is theoretically a risk of reemergence of transmission if a large number of infected individuals migrate from these countries to some of the Pacific Island countries that have achieved elimination of lymphatic filariasis. Therefore, surveillance activities need to be sustained to help early detection of infection, and this needs to be integrated within the health system again as lymphatic filariasis-specific surveillance activities are likely terminated once a country achieve the elimination status.

As new challenges arise, we must join forces with a wide range of stakeholders to identify the most effective and feasible systems/measures to address them. We are continuously building and refining our evidence base to establish the best strategies and guidance for countries. We would like to continue pursuing such pioneering efforts with a hope that the lessons learned in our region can help other disease elimination and control efforts globally in the future.

What led you to work in this field, and what motivates you to continue?

I am not a medical doctor; I am a specialist in the field of environmental and public health. My interest has always been the life cycle of pathogens in the environment. Human pathogens spread through movement between humans, animals, insects, and the environment. We should be able to develop strategies to interrupt the transmission if we fully understand their life cycle and the mechanism of transmission. However, if we cannot do that, infection will continue to spread.

The transmission of parasites is easier to interrupt compared to that of viruses or bacteria because their transmission efficiency is relatively poor for various reasons. If we have a means to interrupt their transmission, we should use it and eliminate the disease. That is our ethical duty.

I had an opportunity to work for WHO while I was a researcher on parasite disease control in Vietnam. I was assigned to the Department of Control of NTDs at WHO Headquarters in 2006 where I met Dr Kazuyo Ichimori, who became my mentor. She taught me everything about the work of disease elimination and eradication and the role of WHO in supporting Member States.

Dr. Ichimori used to say "WHO should be the conductor of an orchestra." Many agencies and organizations are involved in global health, and the number of players keeps increasing. Every player has its own strength and interest as if they have different instruments. WHO should never be the one to play an instrument by itself; instead, WHO should be the one to stay behind and guide each player on when and how best to play their instrument so that all the players join forces and create beautiful music.

In other words, WHO needs to play a leadership role to set out the direction for all the stakeholders and lead them towards a set of common goals by producing evidence-based guidance and identifying the areas for further research. A program where the conductor is fully functioning will be successful. On the other hand, in a program without a functioning conductor, all players began to play as they wish and fail to coordinate and cooperate towards a common goal. Keeping this in mind, I wish to continue working behind the scenes to help as many countries as possible to achieve the NTD roadmap goal for as many diseases as possible.

The affiliations and positions listed in this interview are at the time of publication of the interview in 2017.

- Biography

- Dr. Aya Yajima

Technical Officer

Malaria, other Vectorborne and Parasitic Diseases Unit

Division of Communicable Diseases

World Health Organization Western Pacific Regional Office

Dr. Aya Yajima is the focal point of neglected tropical diseases (NTD) control and elimination in the WHO Western Pacific Regional Office. She coordinates with WHO Headquarters, Country Offices, donors and partners to provide technical support for NTD-endemic Member States in the Region for accelerating control and elimination of NTDs. Formerly she was a technical officer at the Department of Control of NTD, WHO Headquarters where she supported development of various technical guidelines and tools to facilitate and monitor implementation of preventive chemotherapy interventions. She is a graduate of the University of London (Queen Mary) and earned PhD at the University of Tokyo on transmission control of foodborne trematodiases in Viet Nam.

STAKEHOLDER INTERVIEWSARCHIVES

FUNDING

-

01

Dr. Naoko YamamotoSenior Assistant Minister for Global Health,

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

#

-

02

Dr. Hannah KettlerSenior Program Officer, Life Science Partnerships

Global Health Program, Office of the President

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

#

-

03

Prof. Stephen CaddickDirector, Innovations Division,

Wellcome Trust

#

DISCOVERY

-

01

Dr. David ReddyCEO

Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV)

#

-

02

Mr. George NakayamaRepresentative Director,

Chairman and CEO

Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited

#

-

03

Prof. Kiyoshi KitaProfessor Emeritus, The University of Tokyo

Professor and Dean, Nagasaki University School of Tropical Medicine and Global Health

#

DEVELOPMENT

-

01

Mr. Christophe WeberRepresentative Director, President and CEO

Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited

#

-

02

Mr. Yoshihiko HatanakaRepresentative Director,

President and CEO

Astellas Pharma Inc.

#

-

03

Dr. Nathalie Strub WourgaftMedical Director

Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi)

#

ACCESS

-

01

Dr. Jayasree K. IyerExecutive Director

Access to Medicine Foundation

#

-

02

Mr. Tetsuo KondoDirector

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

Representation Office in Tokyo

#

-

03

Dr. Aya YajimaTechnical Officer

Malaria, other Vectorborne and Parasitic Diseases Unit

Division of Communicable Diseases

World Health Organization Western Pacific Regional Office

#

POLICY

-

01

Dr. Mark DybulFormer Executive Director

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS,

Tuberculosis and Malaria

#

-

02

Dr. Seth BerkleyCEO

Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance

#

-

03

Hon. Prof. Keizo TakemiMember of the House of Councillors of Japan

Chairman, Special Committee on Global Health Strategy

of the Liberal Democratic Party's Policy

#